How do Non-Governmental Organisations Execute Shareholder Activism in order to Create Corporate Social Responsibility?

Vincent Becker - 2023

Abstract:

This paper examines how NGOs execute shareholder activism to foster CSR and discusses the effectiveness of this method. Additionally, four different approaches in which NGOs can execute shareholder activism are covert, namely as advocate, as advisor/consultant, as shareholder or as sponsor of CSR funds. Respectively, these approaches increase in their commitment and direct influence and except the advocate approach, they all have a collaborative nature. Finally, this paper concludes that even though there are regulatory difficulties, shareholder activism by NGOs is an effective tool to foster CSR, mainly because of its ability to draw attention and create pressure.

Introduction:

Shareholder activism is a tool predominately operated by institutional investors, to influence management decisions to increase shareholder value (Black, 1997). Nevertheless, shareholder activism is increasingly being used to pursue other goals, one of which is corporate social responsibility (CSR) (Sjörström, 2008). Initially, CSR was conducted by individual investors, now, however, numerous institutional investors strive for this goal as well (Bratton & McCahery, 2015). These institutional investors can be divided into two types: pro-profit and non-profit non-governmental organisations (NGOs). This research will concentrate on NGOs that use shareholder activism to foster CSR in firms.

Historically there was always shareholder activism by non-profit interest groups (such as unions), however, these initiatives were only to yield value for internal stakeholders (Sjörström, 2008). NGOs that specified on creating CSR through shareholder activism for all stakeholders emerged in recent decades. This recent emergence is highly impactful because it affects all three dimensions of the triple bottom line. It is a topic that is interesting from a societal and environmental, as well as from a business perspective.

This research will elaborate on shareholder activism, NGOs, and CSR individually and afterwards exemplify how these concepts cooperate. Furthermore, this research will examine the different approaches employed by NGOs to execute shareholder activism and illustrate them with specific cases. Lastly, the efficiency of shareholder activism by NGOs will be discussed.

Fundamental Terminology:

In advance of discussing NGO shareholder activism in practice, the underlying concepts must be defined.

Shareholder Activism:

Hirschman (1970) defines two different actions participants in a business (e.g., shareholders, but also customers) can take when a business does not perform in the desired way: to exit or to voice. To exit means to boycott a business and avoid it. For shareholders, this implies selling their shares in the specific business and to move on. Alternatively, individuals and institutions involved in a business can raise their voice. This is what direct shareholder activism is based on. Shareholder activism is when stockholders actively use their ownership position in order to influence companies’ governance, performance, or activism directed towards social goals (Sjörström, 2008; Black, 1997).

To execute their voice, shareholders can either engage in dialogue with management or file a proposal (Hirschman, 1970; Cundill et al., 2018). Forms of getting in dialogue are issuing press briefings, writing articles or addressing issues at conferences (Lewis & Mackenzie, 2000). Proposals on the other hand are presented at the annual general meeting and are voted on by other shareholders or their proxy advisor’s vote (Gillian & Starks, 2007). However, since the mid-1980s shareholder proposals cannot be filed by every investor in the United States (Bratton & McCahery, 2015). Paragraph 240.14a-8 of the SEC regulations limits which shareholders can file a proposal. To file a proposal a shareholder must have held $2,000 in market value for three years, $15,000 for two years, or $25,000 for one year in order to file a proposal. These kinds of regulations impede individual & private shareholder activism.

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR):

CSR is an approach to broaden a company’s scope from shareholder value maximation to value maximation for all stakeholders. Historically it was regarded as an obstacle to shareholder value maximisation (Friedman, 1962), nowadays, however, the CSR approach is believed to achieve average profits (Blomgrem, 2011). Additionally, the CSR approach and its disclosure renders lower cost of equity (Dhaliwal et al., 2011) and therefore boosts companies’ stock price (Arx & Ziegler, 2008).

Non-Governmental Organisations:

Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) are recently emerged actors in the political and business environment. NGOs aim at different social and environmental goals that are often neglected by pro-profit organisations, such as abuses of human rights, environmental issues, or healthcare (Yaziji & Doh, 2009). NGOs try to ensure that every aspect of the triple-bottom-line is respected.

Shareholder Activism in Practice:

Shareholder activism by NGOs became increasingly influential in the modern business world (Guay et al., 2015). However, the approaches of NGOs differ in how NGOs execute shareholder activism.

Attack versus Collaboration:

NGOs can reach their goals in two different ways. They can collaborate with their targets (political institutions, firms, or individuals) or attack them (Teegen et al., 2004). While attack is mostly pure confrontation, the collaborative approach yields sustainable results. Shareholder activism aligns best with the collaborative approach; however, it contains some elements of attack as well.

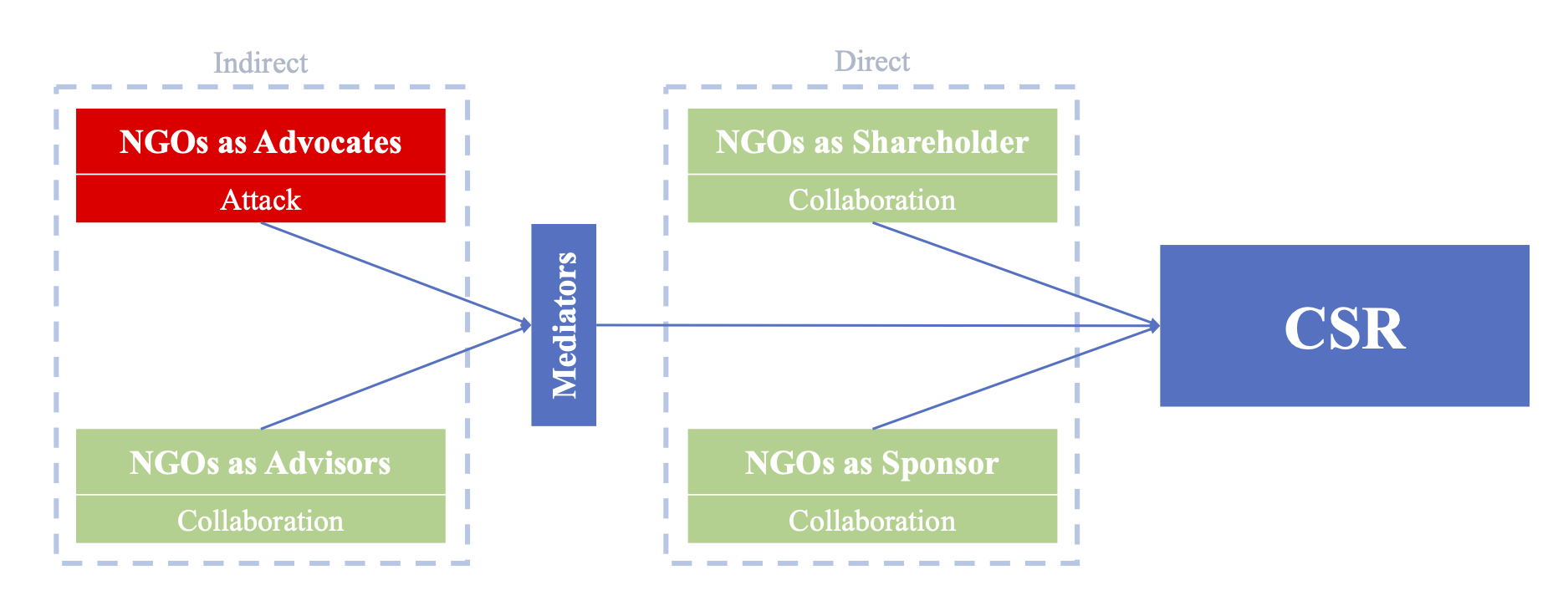

To further specify shareholder activism by NGOs, Guay et al. (2015) define four approaches (Figure 1). These approaches differ in their commitment & direct influence and can be divided into two indirect and two direct approaches to shareholder activism. Direct approaches imply that the NGO functions as shareholder itself while indirect means that it simply influences other shareholders, which then act as mediators.

NGOs as Advocates:

When NGOs act as advocates they pursue an indirect influence on firms. In the position of an advocate, the NGO is promoting CSR with mediators such as pension funds and institutional investors. An example of an NGO functioning as an advocate can be found in the divestment protest in South Africa. The divestment protest in South Africa was an initiative in the 1960s to 1990s to sell shares of South African firms in order to pressure them to oppose apartheid. Supported by NGOs and student movements who pressured pension funds and institutional investors, this advocacy led to many divestments in South African firms (Edgar, 1990). Such an approach could be classified as attacking.

NGOs as Advisors/Consultants:

In contrast to NGOs as advocates, NGOs functioning as advisors pursue a collaborative approach. In this way, they have a stronger influence on other companies, yet still indirect. NGOs acting in this category function as consultants, information analysts and advisors to funds with their scope on CSR.

An example of an NGO functioning as advisor/consultant is the Interfaith Center for Corporate Responsibility (ICCR). In 2017, the ICCR has been advisor/consultant for CSR-oriented funds in 300 shareholder proposals at 177 companies. A prominent achievement applying this method was to get Jack in the Box to phase out the use of antibiotics in their chicken products (ICCR, 2017).

NGOs as Shareholder:

In comparison to the advocate and advisor approach, the shareholder approach entails that NGOs own stock themselves. This allows them to file their own proposals and participate in proxy voting, which provides these NGOs with a very direct influence. For instance, Engine No. 1 (EN1) is a group of activist investors who buy stock in companies to pursue CSR. In early 2021, EN1 filed a remarkable shareholder proposal and succeeded to replace four board members at ExxonMobil with only 0.02% of the shares (Aguirre, 2021). However, it is rare that the shareholder approach is pursued in a pure form. As mentioned earlier, shareholder proposal regulations make it a capital and time intensive task to perform.

NGOs as Sponsors of CSR Funds:

To solve this missing capital and time issue NGOs introduced CSR-oriented funds managed by them. These funds emerged in the mid-1990s and empowered NGOs to invest much more capital to be more impactful. The Human Equity Fund, for example, was introduced by the Human Society of the United States in 2000. It was a fund in which one can deposit money for it to be reinvested in responsible firms to achieve animal welfare (Belise, 2001).

Discussion of Effectiveness:

What all these approaches have in common is that they utilize some corporate control tools to influence governance, the most prominent of which is the shareholder proposal and the following proxy voting. However, a shareholder proposal is not legally binding and is only mandatory to be considered by management in case a majority of proxy voters agree. This missing obligation raises doubt over the effectiveness and sensibility of this tool to push companies towards CSR. ICCR, for instance, collects more than 40% of votes in only 7% of their proposals (ICCR, 2017).

However, this is an inadequate measurement of effectiveness. As we have seen in the Engine No. 1 case, it is not necessary to own many shares to actively pursue shareholder activism. In addition, a shareholder proposal does not necessarily require above 50% in a proxy vote to be recognised and addressed by management. Often issuing the proposal is already sufficient. ICCR, for example, withdrew 30% of their shareholder proposals because other agreements were found (ICCR, 2017). In many cases issuing the proposal draws so much attention from other investors, institutions, media, and society that firms managements succumb to the pressure and implement the proposals (Cundill et al., 2018). This is intended by many investors and is an important motivation behind shareholder activism (O’Rourke, 2003). Therefore, shareholder proposals are a valuable tool for NGOs to achieve their goals.

Conclusion:

Striving towards CSR is at the core of NGOs. Shareholder activism is a tool to achieve this. Mainly using Hirschman’s voice approach, NGOs mostly collaborate with firms in four different ways. They act as advocates and advisors and exert indirect force on companies, or they act as shareholder and sponsor to directly pressure firms. Mostly through shareholder activism, these NGOs are a serious player in today’s corporate governance environment and their importance will probably only increase with growing CSR challenges in the future.

Resources:

Admati, A. R., & Pfleiderer, P. (2009). The “Wall Street Walk” and Shareholder Activism: Exit as a Form of Voice. Review of Financial Studies, 22(7), 2645–2685. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhp037

Aguirre, J. C. (2021, October 13). The Little Hedge Fund Taking Down Big Oil. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/23/magazine/exxon-mobil-engine-no-1-board.html

Belise, L. (2001). Rise of the Name-brand Fund: A Few Aurity Groups Help Investors Put their Money where their Hearts are. Christian Science Monitor, 16.

Black, B. S. (1997). Shareholder Activism and Corporate Governance in the United States. Social Science Research Network. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.45100

Blomgren, A. (2011). Does corporate social responsibility influence profit margins? a case study of executive perceptions. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 18(5), 263–274. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.246

Bratton, W. W., & McCahery, J. (2015). Institutional Investor Activism: Hedge Funds and Private Equity, Economics and Regulation. Oxford University Press, USA.

Briscoe, F., & Gupta, A. (2016). Social Activism in and Around Organizations. The Academy of Management Annals, 10(1), 671–727. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2016.1153261

Cundill, G., Smart, P., & Wilson, H. R. (2018). Non-financial Shareholder Activism: A Process Model for Influencing Corporate Environmental and Social Performance*. International Journal of Management Reviews, 20(2), 606–626. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12157

Dhaliwal, D. S., Li, O. Z., Tsang, A., & Yang, Y. (2011). Voluntary Nonfinancial Disclosure and the Cost of Equity Capital: The Initiation of Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting. The Accounting Review, 86(1), 59–100. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.00000005

Edgar, R. R. (1990). Sanctioning Apartheid. Africa Research and Publications.

Friedman, M. (1962). Capitalism and Freedom. University of Chicago Press.

Gillan, S. L., & Starks, L. T. (2007). The Evolution of Shareholder Activism in the United States. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6622.2007.00125.x

Guay, T. R., Doh, J. P., & Sinclair, G. (2004). Non-Governmental Organizations, Shareholder Activism, and Socially Responsible Investments: Ethical, Strategic, and Governance Implications. Journal of Business Ethics, 52(1), 125–139. https://doi.org/10.1023/b:busi.0000033112.11461.69

Hirschman, A. O. (1970). Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States. Harvard University Press.

ICCR. (2017). ICCR’s 2017 Proxy Season Successes. https://www.iccr.org/sites/default/files/page_attachments/2017 iccrhighvotesandwithdrawals06.26.17.pdf

Levis, A., & Mackenzie, C. (2000). Support for investor activism among U.K. ethical investors. Journal of Business Ethics, 215–222.

Sjöström, E. (2008). Shareholder activism for corporate social responsibility: what do we know? Sustainable Development, 16(3), 141–154. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.361

Teegen, H., Doh, J. P., & Vachani, S. (2004). The importance of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) in global governance and value creation: an international business research agenda. Journal of International Business Studies, 35(6), 463–483. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400112

Von Arx, U., & Ziegler, A. (2008). The Effect of CSR on Stock Performance: New Evidence for the USA and Europe. Social Science Research Network. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1102528

Waygood, S., & Wehrmeyer, W. (2003). A critical assessment of how non-governmental organizations use the capital markets to achieve their aims: a UK study. Business Strategy and the Environment. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.377

Yaziji, M., & Doh, J. (2009). NGOs and Corporations: Conflict and Collaboration. Cambridge University Press.